3D Logic

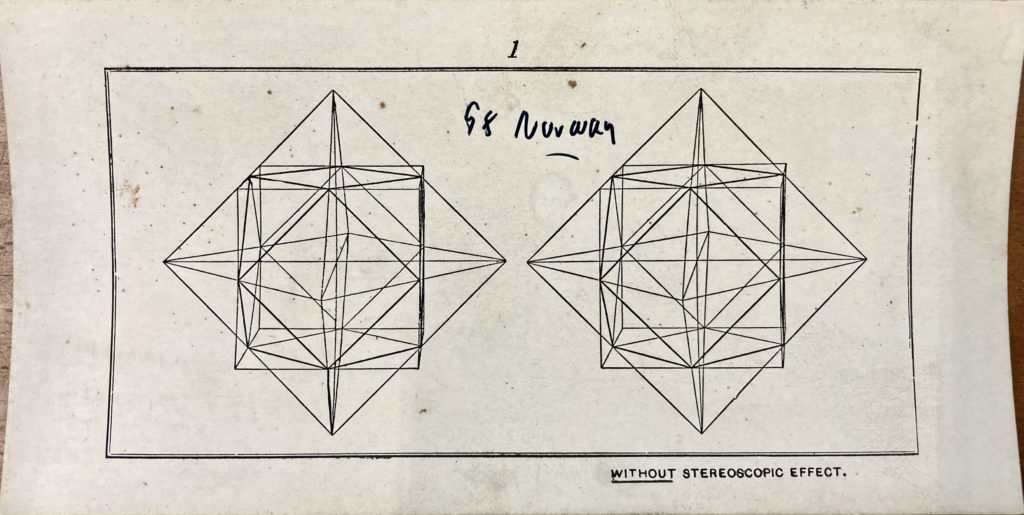

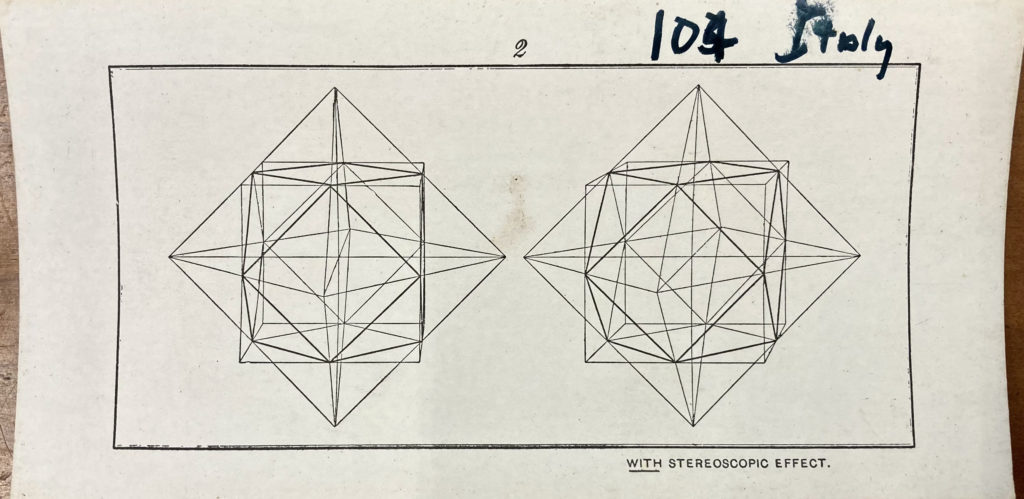

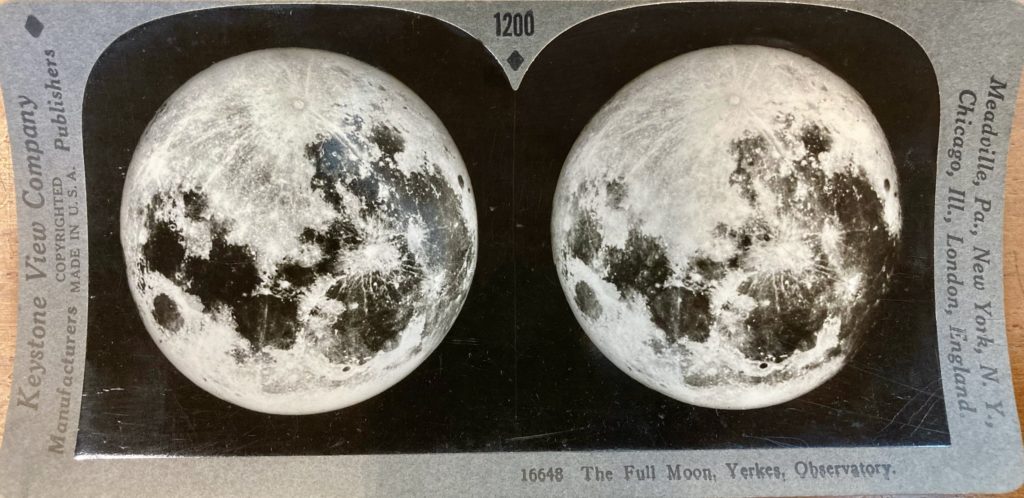

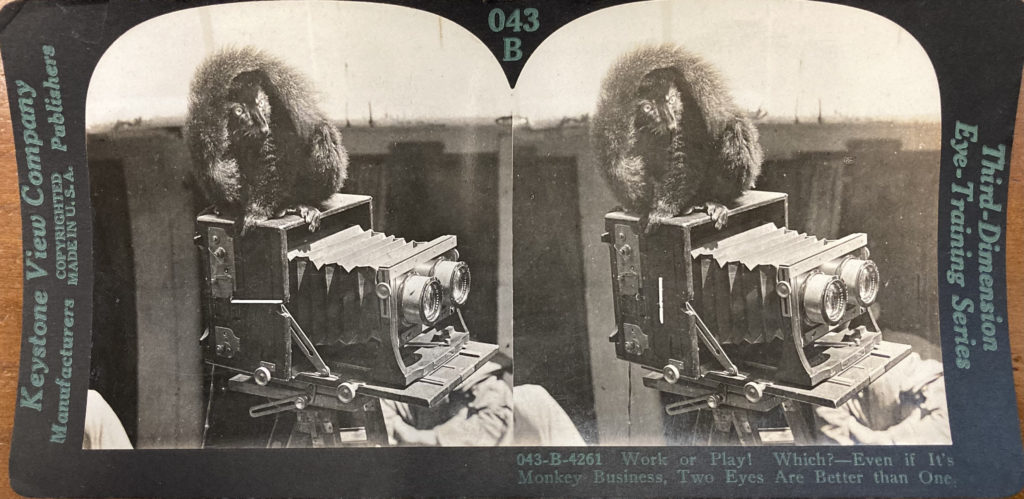

The essential idea behind the stereograph is that having two eyes to see something from two slightly different angles produces a 3D effect. Therefore, having two different images side-by-side—taken at slightly different angles—gives the sensation of depth.

Out in the Field

In the early days of stereo photography, views were captured on glass plates. The nonporous quality of glass made for clean, crisp images, although they were fragile and expensive. To prepare, photographers coated their material in chemicals that could capture light—a lot of the same basic steps involved in regular photography of the day. At the scene, a stereo photographer had to prepare, expose, and process the resulting negatives one step right after another. It required equipment that wasn’t always easy to carry around.

What makes stereo photography unique from the regular method is the presence of left and right perspectives. Official stereo cameras have two lenses, which, upon producing a negative, must be transposed. Some photographers got around this by shifting their regular cameras slightly to take two completely separate photos, but it risked improper horizontal alignment that would ruin the stereo effect. Some photographers missed the logic entirely and simply made adjacent copies of the exact same photo. This method makes for “flat” views, which are mentioned under Looking Closely. The types of artistic flare and careful arrangement put into stereo photography are discussed under Tricks and Trends.

Colors

In the early days of photography, photos were black and white. This didn’t stop some stereo photographers from hand-tinting their views, however. Logically, it was twice as much work to color in both sides, and careful precision had to be applied in order for both sides to match.

The early days of photography were also limited by slow exposure, which meant that many active scenes could not be captured, including ever-shifting clouds. When a scenic stereograph of the time was taken, the movement of the clouds caused the sky of the developed image to look solid white. Consequently, some early stereographs have clouds painted in after the fact.