Origins

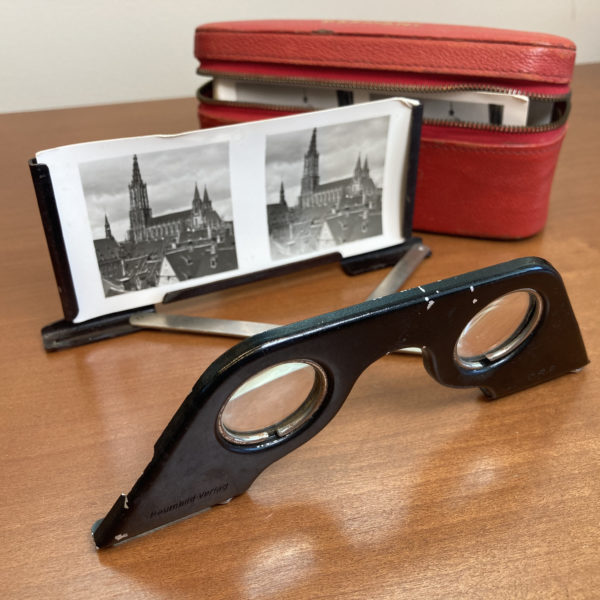

Before stereographs, the only images of other places that were available to the public were woodcut illustrations. Then, in 1839, after Daguerre released the daguerreotype in France, Henry Fox Talbot released his talbotype, and soon after, partnered with a Mr. Collen to introduce a stereoscopic version of it. Stereoscopes—the devices used for viewing stereographs—wouldn’t come until a bit later.

The International Exhibition of London, England arrived in 1851. Sir David Brewster displayed a new stereoscope he invented for easy stereo viewing, allowing the larger public a chance to experience stereographs for the first time. This exposure inevitably led to a massive demand for stereographs by millions of fascinated people.

Increasing Popularity

While the market for stereographs was flourishing in Europe, William and Frederick Langenheim debuted as stereo photographers in America in 1854. Other photographers and publishers quickly rose to the task as it was clear stereo viewing would prove to be a very profitable cultural phenomenon. Collectors emerged in response, one of them being Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes. He realized the stereoscope could be refined even further and sketched an idea that was taken up by stereograph distributor Joseph L. Bates. Bates made some tweaks to the design before sending it to the market, which brought them both success. This design was not only less bulky, but cheaper, making stereo viewing even more accessible.

Similar to how most households today can be counted on to have a TV standing front and center in their living rooms, stereographs became a common form of entertainment in nineteenth century homes. At first, however, this was only true for upper and middle class families.

Economic Constraints

Stereo viewing, and collecting especially, was initially an expensive hobby. This didn’t help the stereograph market when the financial crash of 1873 happened. Suddenly, demand for stereographs had diminished, and many photographers had to go out of business. As a workaround, some pirated copies of preexisting stereographs were distributed, allowing for a cheaper price, but in exchange for a markedly lower quality. Interest in stereographs was still popular, but hindered by this financial strain.

Then, in the 1880s, stereograph publishers began selling door-to-door. This method ensured that any possible customer was confronted personally, sold first a stereoscope alongside a sample of views, then revisited later for more. This gave birth to selling stereographs in series, starting typically in batches a half or full dozen, then increasing to other multiples of six up to a seventy-two set “Tour of the World” series sold by Underwood and Underwood in 1897. They thereafter broke the tradition of sixes with a 100-piece “book box” set, which is elaborated on under Tricks and Trends.

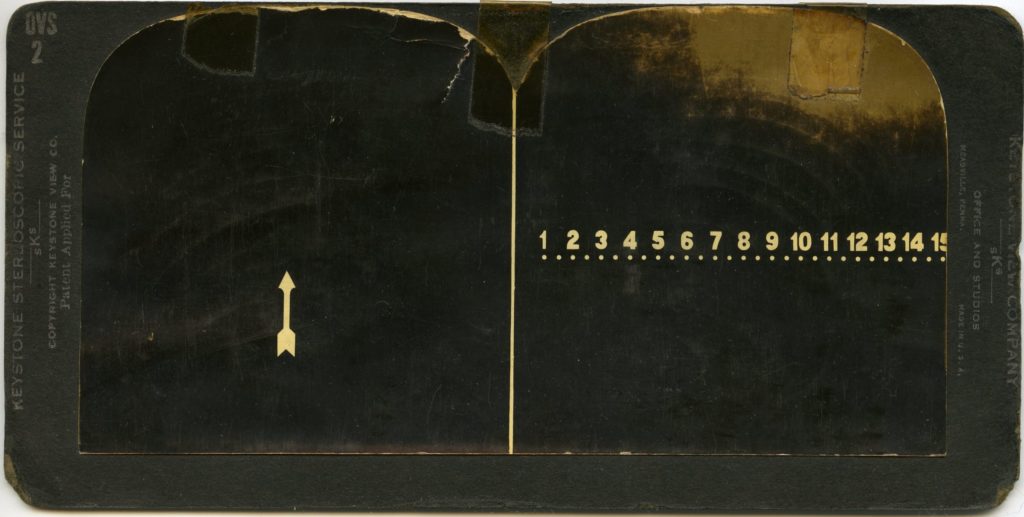

The mass production of stereographs eliminated independent publishers and led companies to compete with one another, Keystone turning out to be the reigning champion. However, the Great Depression hit in 1929, causing another decline in demand for views, which were now unable to compete with radio, magazines, and movies. Keystone had to convert to the production of eye-testing equipment as the stereograph market faded.

Notice, between these identical views, that the first is credited to the company Underwood & Underwood with a note of copyright along the bottom to Strohmeyer & Wyman. The second is distributed by Keystone with a subtitled acknowledgement of copyright to Underwood & Underwood.

Modern Viewing

The general fascination with 3D pictures did not go away. Tru-Vue was popular during the 50s and 60s, and there are still many who remember the View-Master with its familiar paper dial of stereo photos. The recognizable red-and-blue method of 3D effects, requiring corresponding glasses, has been well-known in regards to movies. Additionally, with the rise of the internet, there has come the phenomenon of the stereogram. This is a colorfully-patterned image that does not require two distinct images or a special device. Instead, it relies on its patterns to draw the eye into making out the “hidden” 3D image. Below are three examples generated using an unaffiliated website.

Click on the images to view them up close. The way your eyes move to make out the 3D image is the same way they move when free viewing a stereograph, which is explained under Looking Closely.

After 1930 was when people began considering stereographs for their historical significance instead of just as a parlor trick. The National Stereoscopic Association (NSA) was founded in 1974 and still operates today, publishing a magazine called Stereo World.

Historical Value

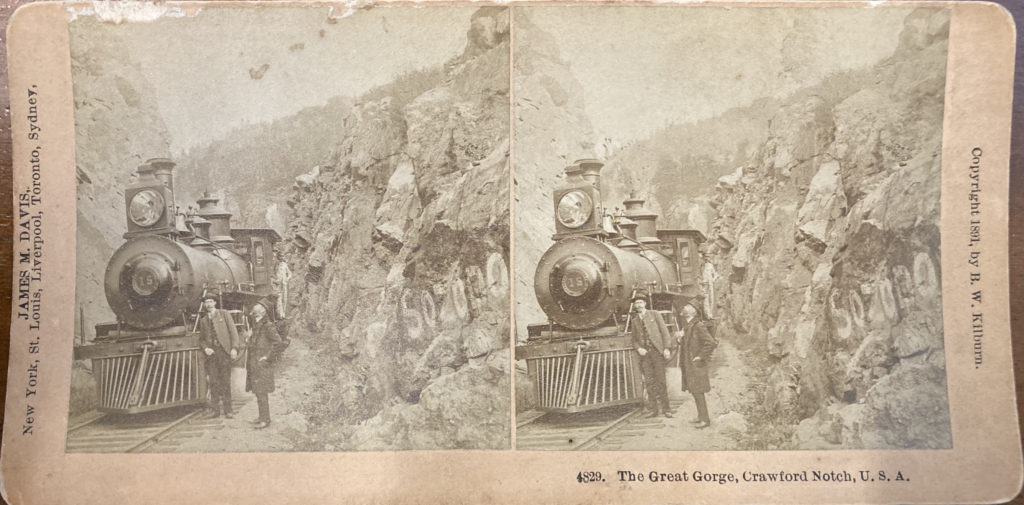

Due to the accessibility these unique photographs offered nineteenth century people for witnessing things they would otherwise require an unlikely trip to see in person, there are a lot of stereographs taken of significant events, places, and people. The Civil War was a major occurrence from 1861-1865 to be documented by various stereo photographers, although they never captured live battle, considering the nature of the photographic process which can be read about under How It’s Done. Abraham Lincoln was stereo photographed, as were many other presidents. The series mentioned above like “Tour of the World” were often centered around tourist attractions in countries foreign to the viewer.

While these major subjects are just as useful to the present-day person looking back on history as they were to the limited citizen of the nineteenth century, modern folk can also learn something from subjects which used to be considered commonplace. What a stereo photographer in the 1800s thought of as mundane was not frequently given much attention, but things like the railroad which have become distant to modern Americans can have their entire history retraced through stereographs. Just as well, via the more artistically-inclined stereo photographer, arranged domestic scenes become a preserved glimpse of day-to-day scenes in the past.