The Beginnings

The Land Ordinance of 1785, a resolution written by Thomas Jefferson to enact a policy of surveying and selling land, was the advent of financing public education in the United States. The Ordinance entailed the selling of the sixteenth section of each township to obtain funding for public education. The profits provided the resources to purchase building materials for schoolhouse sites and to pay teacher salaries.3

This process began in Missouri after 1821 when its statehood began. In 1841, the establishment of Adair County took place in the Northeast part of the state. The County received its name in honor of John Adair (1757-1840). He was a prominent military veteran before serving in the Kentucky House of Representatives, in the United States Senate, and in the Kentucky Governorship.3

Adair County residents gave some of their resources to add to the profits from the selling and leasing of the sixteenth section of the County. However, there was not enough money to provide free public education for all children.3

Until 1865, most schools in Adair were private and financed by parents who could afford the subscription fees. Families held these subscription schools their homes. Then, Article IX of the 1865 Missouri Constitution mandated that public schools receive dividends from local taxes paid by county residents. This increase in funding meant more children could be educated in free schools.3

In 1870, Missouri adopted laws to regulate school boards, the entities that controlled school districts. Local residents voted board members in annually. They were mostly farmers. Among other duties, board members organized meetings, hired teachers for schools, repaired and furnished schoolhouses, and estimated district expenditures. 3

The Schoolhouses

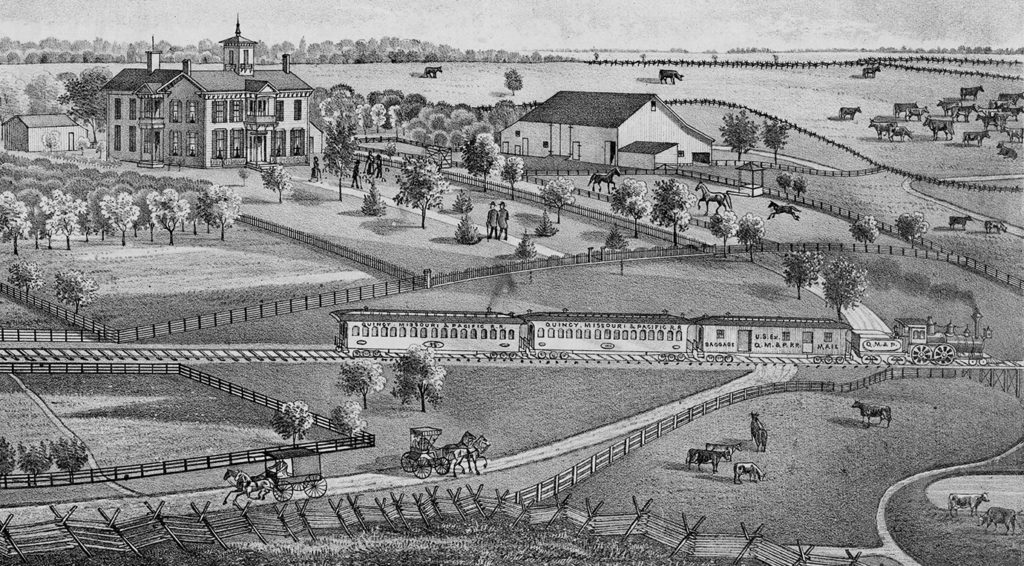

School boards had the key responsibility of building schoolhouse sites. To build one, boards accepted donated land or purchased property with their funding. The optimal location for a school site was as close to the center of the school district as possible so most students would live within a 1.5 mile radius of the site.3

Schoolhouses were large enough to accommodate 30 to 50 students. Most frequently, they were 24” X 36”, 20” X 30”, or 18” x 32” feet. These sites were in the shape of a rectangle to provide optimal acoustics for teachers and students to hear each other.3

Building a schoolhouse site was a community affair since its primary funding source was tax levies. As many residents were farmers with small incomes and humble lives, they were not in favor of spending lavishly on schoolhouse sites. Residents wanted sites that were easy to construct, simple in design, and inexpensive to build.3

To achieve this, residents collected building materials locally. They gathered clapboard for exterior walls, native wood for rafters and sheeting, and red cedar for shingles. They coated interior walls in plaster and then painted or covered them with wallpaper. Finally, they painted the schoolhouse exterior white. The overall simplicity in construction meant it was possible to build a site in just a few weeks.3

Schoolhouses furnishings were just the essentials: desks, hand bells, blackboards, textbooks, and pencils. Teachers made do with what school boards could afford to provide.3

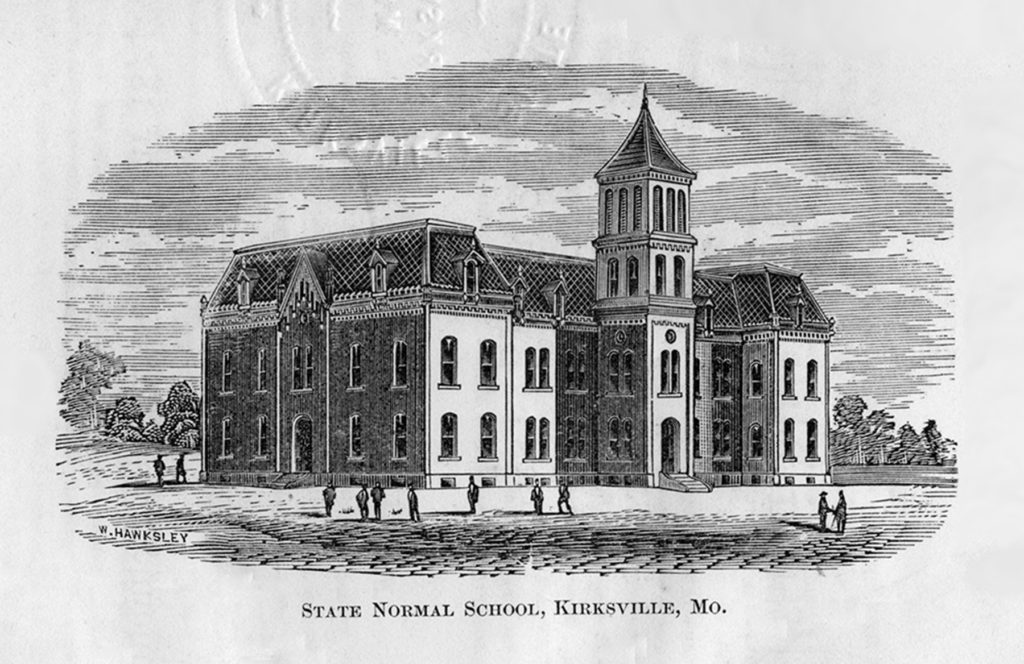

The Schoolteachers In 1870, the Missouri General Assembly selected the private teacher’s college in Kirksville (the County seat of Adair) to be Missouri’s first official “State Normal School”. It thus adopted the name "First District State Normal School". Normal schools were teacher’s colleges that instructed students in the “norms” of pedagogy, the theory and practice of education and teaching.3 The Normal School offered two courses of study for high school graduates who desired to become teachers: a two-year elementary course program and a four-year scientific course program.3 Upon obtaining the two-year degree, graduates received a certificate permitting them to teach in Missouri rural schools for four years. After earning the four-year degree, graduates received a life certificate qualifying them to teach in Missouri rural schools with no subsequent examinations.3 Typically, schoolteachers boarded with a family who lived in the school district. Most were unmarried women with contracts that barred them from entering marriage during their time at the school. A number of women married someone close to their boarding family and stopped teaching as a result. School boards struggled to retain specific teachers for multiple years.3

The Students Schoolchildren began their days around sunrise to complete a number of chores. Then, they walked up to two miles to school, rain or shine. School days were usually 9:00am to 4:00pm.3 In 1907, Missouri established a law that required school terms to last eight months of the calendar year. Typically, it ran September through April. By not attending school during fall harvesting and spring planting, children could assist their families with various farm duties.3 Students learned the basics of reading, writing, and arithmetic. Assignments were ungraded. Teachers followed education competency guideline standards set forth by the state of Missouri. This meant that students were permitted to move at their own speed academically.3 After 8 years in the one-room rural schoolhouse, graduates could enter high school. Secondary schools did not charge tuition but the price of purchasing required textbooks and supplies deterred many from pursuing secondary education.3