In the summer of 1912, Marie accepted a position as the main teacher at the Porter School located four miles northwest of Kirksville in a very poor rural area.1

Marie negotiated with board members to include these two stipulations in her contract: she could alter the curriculum and pedagogy as she saw fit to create an ideal rural school, and she would receive assistance to find a house to rent in the Porter area. Marie signed a three-year contract at a salary of $50 per month.1

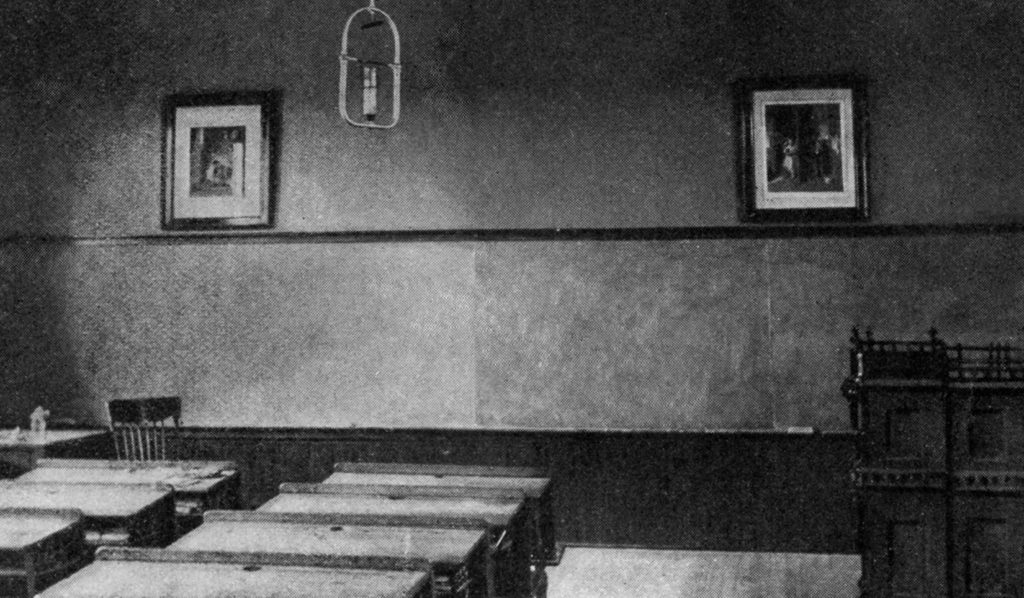

When Marie entered the Porter community, many residents voiced worry about her immediately announced desire to renovate the dilapidated schoolhouse. Not wanting to alienate the community, she did not seek a tax increase. Instead, she asked residents to pitch in whichever resources they could offer to renovate the schoolhouse site. People donated all the extra supplies, labor time, and construction expertise they could give.1

Marie’s renovation strategy strengthened the comradery among community members. After much renovation, the Porter School re-opened in October 1912.1

Students received transport to and from the schoolhouse in a horse drawn wagon.1

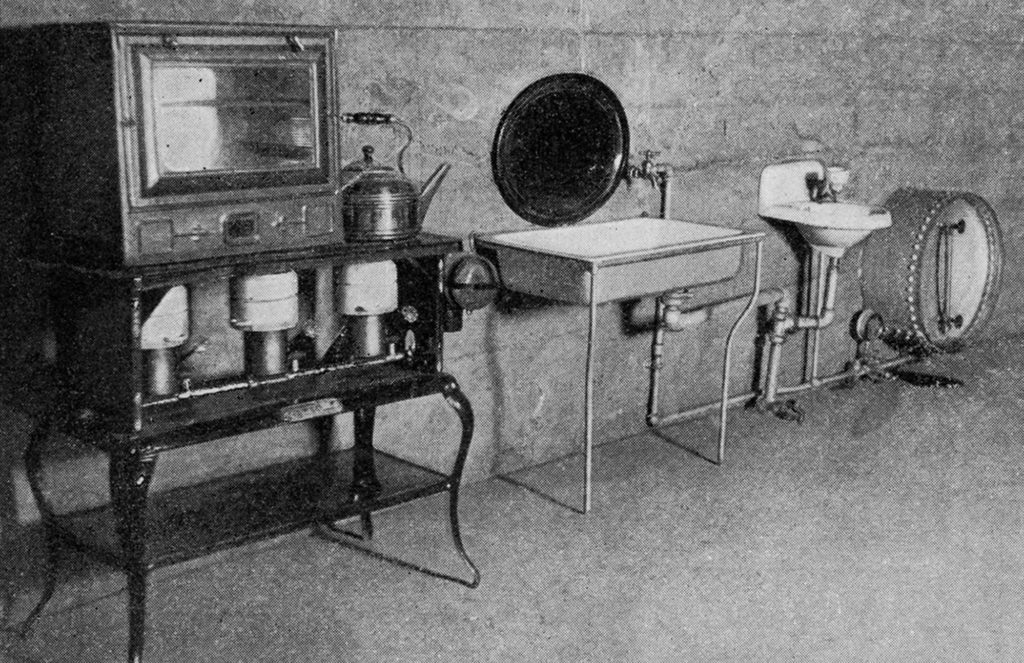

Marie implemented a curriculum similar to the one utilized at the Model Rural School. It included the “practical subjects” of cooking, gardening, and animal husbandry. The assignments she gave for the “basic subjects” of reading, writing, and arithmetic used material from the “practical subjects.” 2

Marie fostered an environment that considered rural living as a worthwhile and exciting adventure. Some of her methods were quite uncomplicated. For example, she encouraged her students to find enjoyment in the modest playground equipment at Porter. One could have fun without the fancy trappings of city entertainment! She believed that once students adopted this attitude, they would want to reside in the country long-term and pursue paths in farming, agriculture, and home-making.2

Marie exposed her students to the widest range of learning opportunities as possible. She infused music and theatre into her curriculum. She organized bands and singing groups, and had the entire class put on plays. Marie participated alongside her students. She played the piano during music time and put on various costumes to act out historical figures during history lessons.2

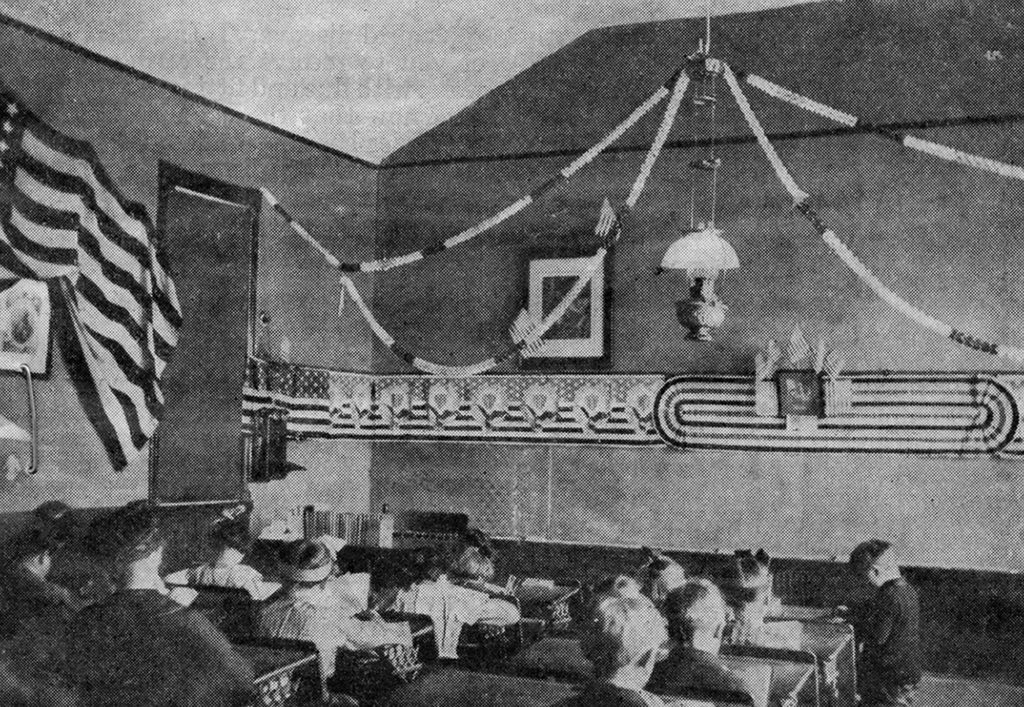

Thanks to Marie’s clear vision, shaped by her time at the Model Rural School and her mentor John Kirk, she successfully transformed the Porter School into her notion of an ideal rural school (crucially, with the help of countless residents). These collaborative efforts created a school to serve as the center of the community. In fact, many residents occupied the schoolhouse for various social gatherings held throughout the year, such as holiday parties.1

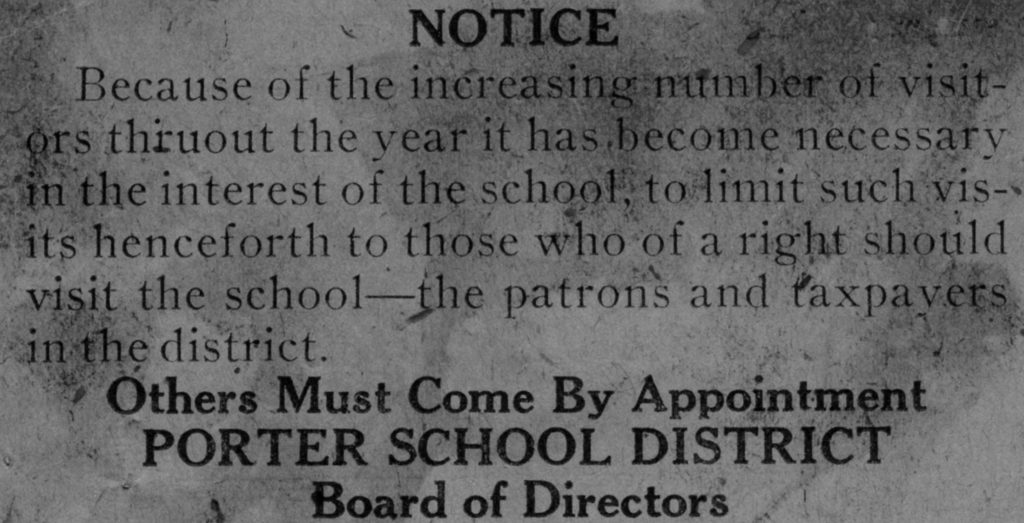

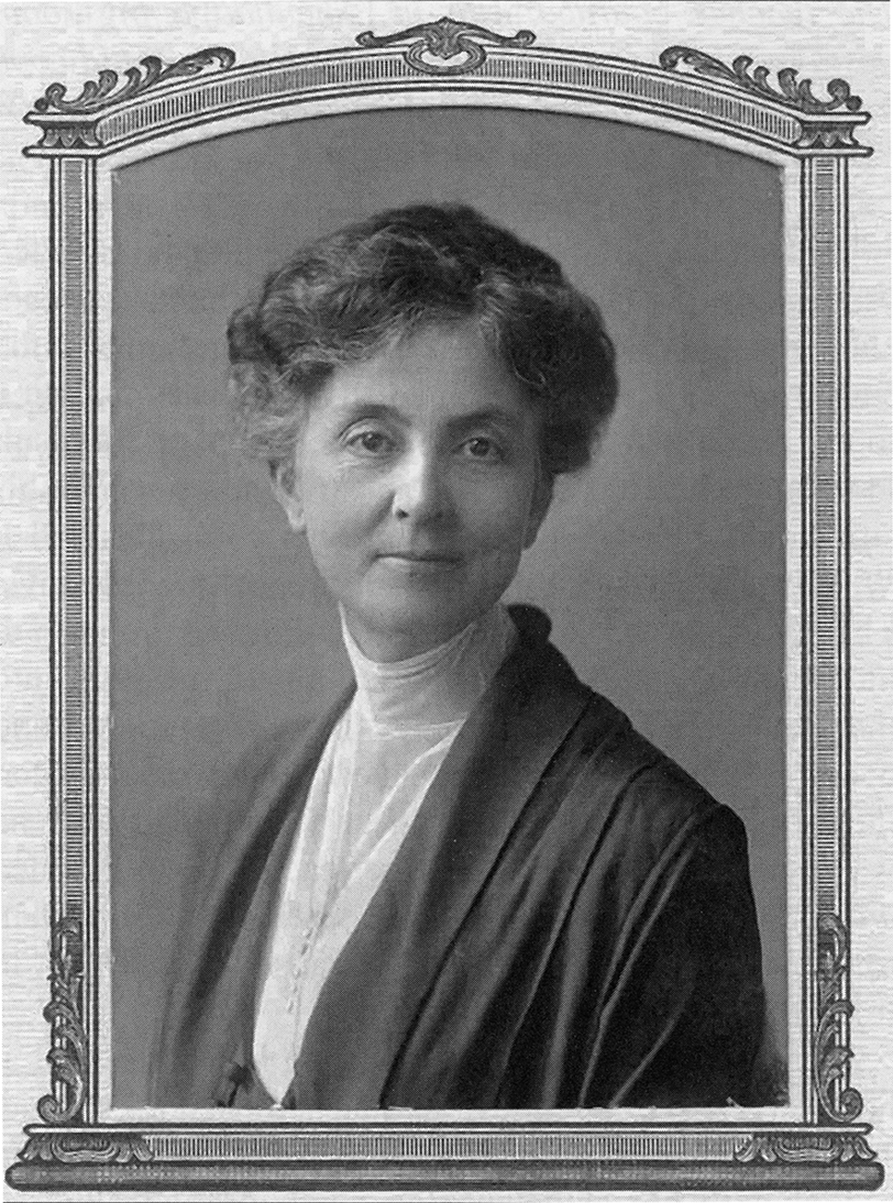

Over the course of several years, Marie achieved her overarching goal: transforming the Porter School to better serve the community’s interests. This did much to raise Marie’s clout as a rural educator and a pioneer for progressive education and pedagogy. Her teaching methods at Porter received national and international attention. Fellow educators traveled far and wide to see the School first hand. Porter received as many as 600 visitors per year.1

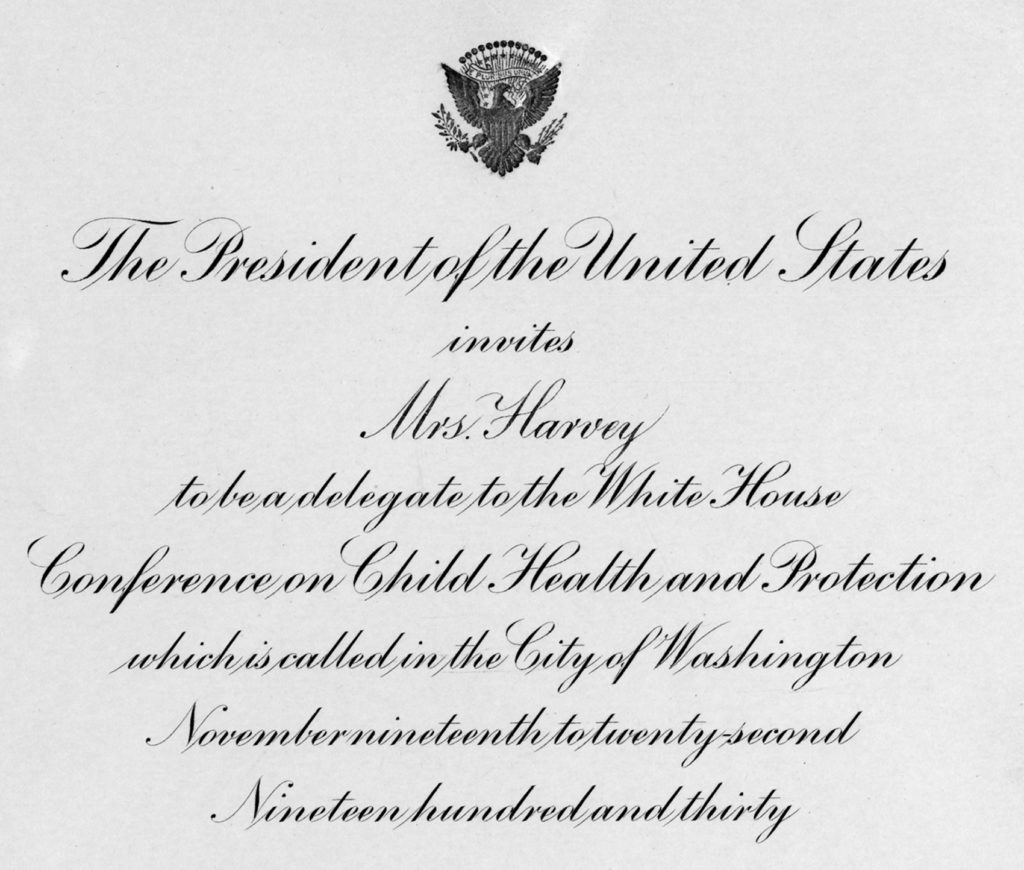

Before long, Marie’s writings appeared in numerous farm and education journals. The U.S. Bureau of Education named her Special Contributor in Rural Education. She served on the White House Conference on Child Health and Protection at the invitation of President Herbert Hoover. And while she was still teaching full time at Porter as the main teacher, Marie managed to find time on the weekends and in the summers to travel to 21 states across America for speaking engagements, teaching workshops, and curriculum seminars. Her work ethic had no peer.1

Marie’s teaching philosophy had this overall mission: to teach in a way that serves the interests of the community at hand and educates its students on how to do the same. At the Porter School, she took her students’ need to learn the core components of rural life such as gardening, animal husbandry, and cooking, and their need to master reading, writing, and arithmetic skills, and then enmeshed the two set of needs in every lesson she taught.2

By introducing lessons on manners, respect, and country values, Marie taught her students to interact with other people, both similar and otherwise. By incorporating music and theatre into her classroom, she set the tone that rural life is exciting and worth preserving. Marie was a rural education pioneer in every regard. She taught at the Porter School until her retirement in 1924.2

To learn more about the history of Adair County and rural education in Missouri, or to read more about John Kirk and Marie Turner Harvey, please visit the Special Collections Department in Pickler Memorial Library at Truman State University:

100 E. Normal Ave., Kirksville, MO 63501

Located in the West area of third floor

Open Mon-Fri, 7:30am-5:00pm

speccoll@truman.edu

(660) 785-4537