Pauline Dingle Knobbs

Transcript

This is Pauline Knobbs speaking for the Adair County Bi-centennial Committee in the subject of the big fire, which was the fire which burned Baldwin Hall to the ground.

On the afternoon of January 23, 1924¹, I was seated in Professor Joseph Lyman Kingsbury’s class in Social and Economic American History in the eighth grade room of the old practice school on the northwest corner of the second floor of the Library Building. The door suddenly burst open and an excited young man yelled, “Old Baldwin is on fire! on the third floor! Everybody out!” Professor Kingsbury, with a wild gesture, threw up his hands and said, “It’s those damn boys smoking in the wardrobe, and it’ll go like nobody’s business.” And go it did.

When I got outside and looked up at the building, a wisp of smoke was coming out of the window next to the tower on the east side. I laid my books down under a tree near the lake and followed the students in through the tower door on the main floor to see how I could help save some of the materials in Professor Violette’s museum. A group of us carried out maps, charts and artifacts and placed them near the lake.

Meanwhile, the fire department had arrived and attached hoses to the hydrants on the east side of Baldwin, but only a small stream of water, about the size of a garden hose, came out. A new pumper-truck had just been secured for the department but no one in Kirksville understood its operation. Nevertheless, a hole was cut in the ice of the lake and the firemen tried valiantly to add pressure to the water, without much avail. A wild call was sent to Macon and Moberly for help, and at Macon an engine was detached from a Wabash freight train and the Macon fire Department firemen were loaded on a flat car and brought at full steam to Kirksville. Upon arrival, one fireman got the pumper truck working with a good stream of water from the lake and this was played on the fire.

Meanwhile, Baldwin was flaming. As faculty and students sought to save belongings, John Jack and Johnnie Gill, the two chief custodians, ran down the second and first floor halls and into the basement crying, “Everybody out! Everybody out! There are a dozen three-thousand pound radiators on the third floor that will crash through to the basement any minute carrying flaming timbers with them.” So everyone fled. I remember the acrid black smoke on the first floor of Old Baldwin and the stifling gases as I helped Dr. Clara Howard, later Dr. Clara Howard Clevenger, carry her briefcases out the corridor to the Library Building exit-way. The fire chief had dynamite ready to blast this corridor and save the wonderful Library — Science Hall (now Laughlin) had fire doors on the corridors at the end still standing that kept the flames from burning that building — but President Kirk stopped the dynamiting, saying it would abrogate the insurance policies.

Meanwhile, long lines of men had formed and were carrying books, armload after armload, from the library as others threw books from the windows to sheets held by students below. Then President Kirk appeared and ordered this stopped, saying again it would abrogate the insurance policies. Many of us stood with tears streaming down our face and watched that wonderful library of rare books and periodicals go up in smoke.

When it became evident that Baldwin and the Library were gone, streams of water were played on the east side of Laughlin and the west side of Kirk Auditorium (only lately finished).

I ate a bite of supper at the Newman Cafeteria located in the now Williams apartment building, took my books home, and returned to the campus.

It was an eerie scene as night fell and the buildings burned on. I can see President Kirk now, standing on the second floor of Old Science Hall, arms folded across his breast like Napoleon at Waterloo, gazing into the blazing inferno that had been Baldwin Hall.

I left the campus about 10:30 p.m., wondering where I would finish my senior year, for I was in the second quarter of that year.

Next morning the town was plastered with handbills announcing that a faculty and student meeting would be held in Kirk Auditorium. The esprit de corps was wonderful as faculty member after faculty member arose and pledged his allegiance, and student group after student group likewise pledged their undying devotion to the old school.

All that was left was Ophelia Parrish Building, Kirk Auditorium, Old Science Hall (now Laughlin Hall), the Power Plant and the Model Rural School, at the southeast corner where the McKinney Hall now stands. But the librarians reordered books and townspeople, churches, lodges, offered their halls and soon the Northeast Missouri State Teachers College arose, phoenix-like, from the ashes and was a going concern.

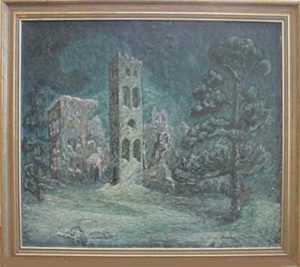

Winter continued the same, and snows fell to cover the wounds of the Library and Old Baldwin, and Charles Henry² painted a picture of those. The loss of the tower and the Library were our greatest anguish, but time healed and these became a thing of precious memories, only. And the great fire passed into oblivion.

We graduated in May and in August, but there are no 1924 yearbooks, for Edwin “Pete” Myers and his staff did not save them or the dummies of them, from the “big fire”. Thus memory of the 1924 class is all that is left of the yearbooks.

1. The actual date of the fire was January 28, 1924.

2. Dr Knobbs probably refers to the Archie Musick painting commissioned by the class of 1928, found at the top of the page.

Pauline Dingle Knobbs, PhD, Professor of Social Science Education

About the speaker: Miss Pauline Dingle, a student from Palmyra, MO, was in class when the fire started. Fifty-two years later, Professor Emeritus Pauline Dingle Knobbs recorded her memories of that day for the Adair County Bicentennial Committee’s oral history project.