Parchment and Ruling

Scriptoriums

Books during the Middle Ages were often produced in scriptoriums which were typically found in monasteries and other ecclesiastical institutions as they were major centers for learning. [1] During the eleventh and twelfth centuries lay scribes and illuminators would travel to monasteries due to this.

However, around the year 1200, books began being produced by lay people who had established themselves in certain cities and made it their sole job to create books. Books were continuing to be made by clergymen as well as monks during this time as well. [2]

The Use of Vellum

While paper was known during the early Middle Ages it was not produced in large quantities and became more established with the development of printing. [3] As such, Books of Hours and manuscripts during this time were made out of vellum.

Vellum is typically made from the skins of sheep or calves and it is the size of this animal that denoted the maximum size of a book. [4] Smaller books could have several pages cut from one skin while the larger books could have a sheet represent one animal. [5]

To learn more about vellum follow this link:

The Making of Ink

In order to make ink one would use carbon and add gum and water to create a permanent black. Or they could make it using iron gall which is sulphate of iron and oak apples and then add gum and water to produce a brownish tint. [6]

In order to make colored ink the user would have to gather the proper materials. Colored ink is made from a variety of substances, like animal, vegetable, and mineral. [7] These substances could be commonly found, but some were located much farther away. Lapis lazuli, which creates a deep blue ink is a mineral that could only be found in mines in Afghanistan. [8]

In order to create a gold ink the user would need to ground the mineral into a powder and mix it into paint or have the mineral beaten into a leaf which would then be laid over and adhesive ground and then burnished. [9]

Lettre Bâtarde

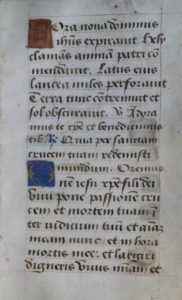

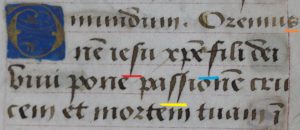

Lettre Bâtarde or lettre bourguignome [10] is the script used in this Book of Hours. It is characterized by the tall s and f that fall below the line. [11]

This script began being used in Flanders during the 1400s. [12]

There are several other characterizations that is typical of this script such as with the letters v, q, a, and d and others. [13] Within Figure 1 the focus will be on the different ways s and f are shown.

Above is text taken from Figure 1. Within this text are examples of lettre bâtarde script.

- In red is the letter s.

- In yellow is the letter s followed by another s.

- In orange is the letter s which is commonly used at word endings instead of the tall s seen in red and yellow.

- In blue is the letter f.

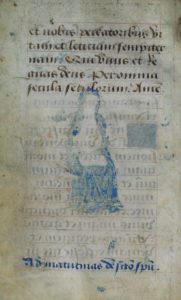

Making an Illumination

The illustration within Books of Hours is not just called an illustration it is also referred to as an illumination. Illumination is defined as the art of decorating books with colors and metals. The metals used are usually gold and occasionally silver. [14] Within this particular Book of Hours gold illumination can be seen on The Annunciation to the Virgin Mother, The Visitation, and the Adoration of the Magi.

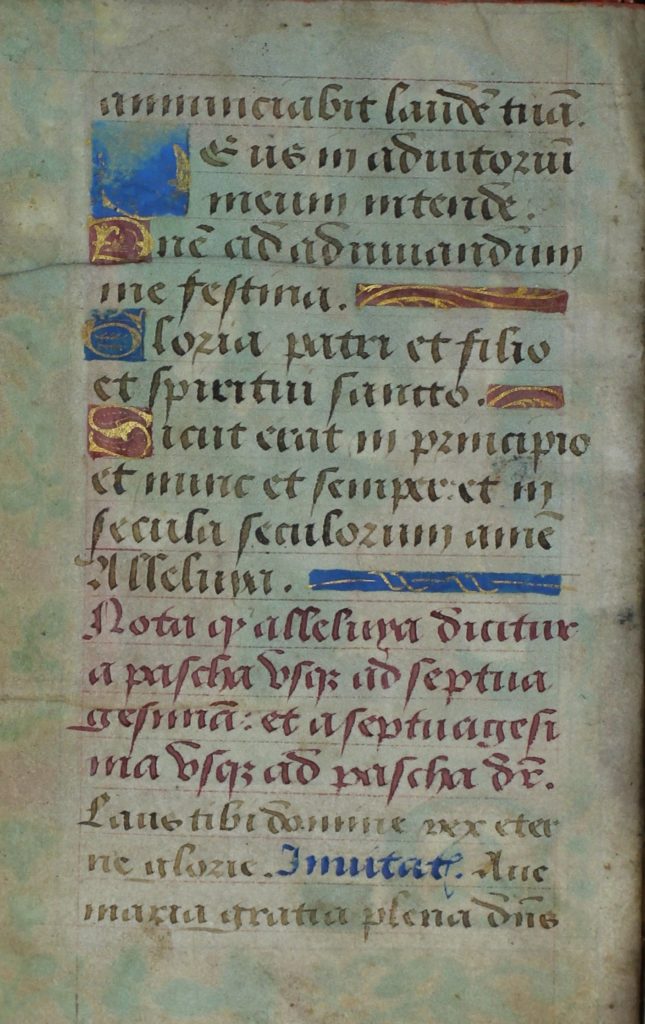

Initials

Illumination is not just found in the illustrations found in Book of Hours, but also within the text by use of initials. Initials are used to make a division of text which separates chapters, paragraphs, and other sections. [15] The important sections are usually decorated as can be seen with the Initial from the Annunciation of the Virgin Mother. The lesser initials were typically made up of colored letters on colored or gold grounds with can be seen with Digital Images 51 and 33.

These simple initials in alternating red and blue with the letters in gold can be found over several centuries. [16] With the Initial from the Annunciation of the Virgin Mother a plant can be viewed within the initial. This decorative scheme was used widely from the thirteenth century and up to the second half of the fifteenth century. It is often referred to as a vine-leaf initial. [17]

Initials could have been added by the scribe or by a specialist. The specialist was more frequently used during the late Middle Ages and received the work after the scribe had completed the writing. A space would be left by the scribe in the place where an initial was required. [18]

See the Making of a Manuscript

More Information

For more reading on this topic see the bibliographic section for sources used in the content of this page or visit these online sources for more information or further examples of illuminated manuscripts.

More Information:

The Making of Medieval Manuscripts: Lecturer Dr. Sally Dormer

Previous Getty Museum Exhibition on Scriptoriums

More examples of Illuminated Manuscripts:

ILLUMINATED: Manuscripts in the Making at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge

The University of Alabama at Birmingham: Reynolds-Finley Historical Library

Footnotes

[1] Rowan Watson, Illuminated Manuscripts and Their Makers (London: V & A Publications, 2004), 8.

[2] Rowan Watson, Illuminated Manuscripts and Their Makers (London: V & A Publications, 2004), 8.

[3] Janet Backhouse, The Illuminated Manuscript (Oxford: Phaidon Press Limited, 1979), 7-8.

[4] Janet Backhouse, The Illuminated Manuscript (Oxford: Phaidon Press Limited, 1979), 8.

[5] Janet Backhouse, The Illuminated Manuscript (Oxford: Phaidon Press Limited, 1979), 8.

[6] Janet Backhouse, The Illuminated Manuscript (Oxford: Phaidon Press Limited, 1979), 8.

[7] Janet Backhouse, The Illuminated Manuscript (Oxford: Phaidon Press Limited, 1979), 8.

[8] Janet Backhouse, The Illuminated Manuscript (Oxford: Phaidon Press Limited, 1979), 8.

[9] Janet Backhouse, The Illuminated Manuscript (Oxford: Phaidon Press Limited, 1979), 8.

[10] Raymond Clemens and Timothy Graham, Introduction to Manuscript Studies (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007), 170.

[11] Raymond Clemens and Timothy Graham, Introduction to Manuscript Studies (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007), 169-170.

[12] Raymond Clemens and Timothy Graham, Introduction to Manuscript Studies (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007), 170.

[13] Raymond Clemens and Timothy Graham, Introduction to Manuscript Studies (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007), 169.

[14] John Harthan, An Introduction to Illuminated Manuscripts (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1983), 6.

[15] Rowan Watson, Illuminated Manuscripts and Their Makers (London: V & A Publications, 2004), 20.

[16] Rowan Watson, Illuminated Manuscripts and Their Makers (London: V & A Publications, 2004), 22.

[17] Rowan Watson, Illuminated Manuscripts and Their Makers (London: V & A Publications, 2004), 34.

[18] Rowan Watson, Illuminated Manuscripts and Their Makers (London: V & A Publications, 2004), 20.